Tigray is a program dedicated to advancing the rights and leadership of young women and girls across Africa. This initiative focuses on combating gender-based violence, promoting equal access to education and political participation, and empowering girls to become advocates for their own rights. Through mentorship, legal aid clinics, and community-led campaigns, Tigray seeks to dismantle patriarchal barriers and build a new generation of female leaders who are confident, knowledgeable, and ready to lead.

An Evidence-Based Project for the Advancement of Young African Women and Girls

I. Foreword: Investing in Africa’s Youngest Leaders

The Pan African Youth Movement (PAYM) recognizes that the socio-economic advancement of the African continent is inextricably linked to the empowerment of its largest and fastest-growing demographic: its young people. Within this demographic, young women and girls represent an immense, yet largely untapped, reservoir of potential whose liberation from systemic barriers is not only a matter of fundamental human rights but a critical catalyst for sustainable development and social transformation. The persistent and multifaceted challenges faced by this demographic demand a strategic, evidence-based, and multi-pillar response.

The Tigray Project is conceived as a comprehensive initiative designed to address these challenges directly. This foundational report provides a detailed, research-backed rationale for the project’s design and urgency. It synthesizes data from peer-reviewed journals, institutional reports, and expert analyses to establish a compelling case for intervention. By focusing on combating gender-based violence (GBV), promoting equal access to education and political participation, and empowering a new generation of female leaders, the Tigray Project demonstrates a clear, practical, and data-driven imperative for a prosperous, stable, and equitable Africa.

II. The State of Gender Inequality in Contemporary Africa: A Multi-Dimensional Crisis

2.1 The Pervasive Threat of Gender-Based Violence (GBV): A Public Health and Human Rights Catastrophe

Gender-based violence is a significant public health problem and a profound human rights violation with a particularly severe impact in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).1 Findings from a comprehensive study across 25 SSA countries reveal that a notable 44.94% of women have reported experiencing at least one form of GBV.2 This prevalence varies starkly by country, with some regions facing an acute crisis. Sierra Leone, for instance, has a reported prevalence rate of 60.27%, and Uganda 56.92%, while Comoros reports a comparatively lower rate of 10.76%.2 The situation in South Africa is exceptionally dire, with the female homicide rate by intimate partners reported at 24.7 per 100,000 people, more than six times the global average.4 The crisis is compounded by severe underreporting; for instance, the South African Police Services (SAPS) estimates that only one in 36 rape cases are actually reported, suggesting that the true scale of violence could involve millions of additional unreported cases.4 This profound statistical gap is not merely a data point but a clear indicator of a systemic failure to provide a safe and viable path to justice for survivors. The low report rate is a direct consequence of significant barriers, including the fear of stigma and revenge, financial constraints, and a pervasive lack of trust in law enforcement.1 This reality reveals a profound, multi-layered crisis where the problem is not only the violence itself but the societal infrastructure that allows it to flourish in the shadows, where it becomes socially normalized and accepted.5

The manifestations of GBV extend far beyond physical and sexual attacks. The research identifies a wide spectrum of violence, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, as well as forms of intimate partner violence.4 Critical, often-overlooked dimensions include economic violence, which involves controlling or restricting a woman’s access to financial resources, employment, or opportunities to sustain herself.2Moreover, cultural and traditional practices, while sometimes defended as being rooted in heritage, are identified as deeply entrenched forms of violence that violate fundamental human rights and perpetuate cycles of inequality.2 Examples include Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), child marriage, and widow inheritance, which strip women of their bodily autonomy and agency.2

The persistence of GBV is rooted in a complex interplay of individual, community, and societal factors. A lack of education, patriarchal norms, and community-wide tolerant attitudes towards violence are identified as key drivers.1 The evidence suggests that women with lower socioeconomic status and limited education are at a significant risk of experiencing GBV.2 This points to a crucial causal loop: a lack of access to education, justice, and healthcare constitutes a form of “structural violence” embedded within the fabric of society.3 This structural inequality leads to economic disempowerment, which in turn makes young women more vulnerable to direct forms of violence, reinforcing the very structural barriers that created their vulnerability in the first place. The project must therefore frame GBV not as an isolated problem but as a symptom and a driver of broader systemic injustice that requires a holistic response.

2.2 The Systemic Challenge to Educational Equity: Perpetuating the Cycle of Poverty

Despite progress in closing the gender gap in primary school enrollment in some regions, significant disparities in educational access persist across Africa.8 A staggering 9 million girls aged 6 to 11 will never attend school, compared to 6 million boys.10 This gap widens during adolescence, when 36% of girls are excluded from education compared to 32% of boys.10 The long-term consequences are evident in adult literacy rates, where in 2018, there were only 81 literate women for every 100 literate men in SSA.10 The obstacles to girls’ education are not singular but form a multi-headed hydra of interconnected challenges.

Poverty is consistently identified as the single most significant barrier.8 Families struggling with economic hardship often view boys’ education as a better long-term investment, leaving girls at a distinct disadvantage.10 This decision creates a self-perpetuating feedback loop: the initial poverty drives the choice to pull a girl from school, and the resulting lack of education severely limits her future economic opportunities, which perpetuates the same cycle of poverty for the next generation.10 This is compounded by deep-rooted cultural and traditional beliefs that prioritize domestic responsibilities and caregiving for girls, further discouraging their educational pursuits.10

The crisis for girls intensifies during adolescence due to a confluence of risks, making it an intersectional challenge. Practices like early marriage and adolescent pregnancy are major drivers of school dropout, with one in seven babies in East and Southern Africa born to teenage mothers.11 A lack of comprehensive sexuality education and reproductive rights leaves young women vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, which can force them to abandon their schooling.13 This reality demonstrates that a girl’s ability to remain in school is inextricably linked to her safety, health, and bodily autonomy.

The research is clear that investing in girls’ education is one of the most effective solutions to a broad range of socio-economic challenges.8 Studies show that an educated girl tends to marry later, have a smaller and healthier family, and earn significantly higher wages.8 Education has been posited as a “vaccine” against HIV/AIDS, with educated women showing substantially lower infection rates than their non-educated counterparts.8 Investing in girls’ education is not merely a goal in itself but a strategic pathway to poverty alleviation, improved maternal and child health, and the overall economic and social development of a community.8

III. The Human and Socio-Economic Cost of Inequality: A Hindrance to Continental Development

3.1 The Detrimental Health and Psychosocial Consequences

Gender-based violence and gender inequality have severe and lasting consequences for the physical, reproductive, and mental health of women and girls. Physical and sexual violence are directly linked to a heightened risk of unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, and serious pregnancy complications that can be fatal.4 Child brides, for instance, are five times more likely to die in childbirth than women in their twenties, and their children face a 50% higher risk of death in their first year of life.16 The deeply harmful practice of FGM has no health benefits and can cause lifelong physical and psychological trauma, including chronic pain, infections, and obstetric complications.17

Beyond the physical harm, the psychosocial impact of GBV is profound and pervasive. The research consistently links exposure to physical and sexual violence with a host of adverse mental health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and a heightened risk of suicidal behavior.2 The trauma can lead to radical changes in a victim’s self-image and their feelings about the past, present, and future, creating feelings of worthlessness, shame, and social isolation.5 Furthermore, a history of sexual abuse is associated with subsequent high-risk behaviors, such as alcohol and substance abuse, and a greater likelihood of entering into abusive relationships later in life.15 This suggests that the trauma of GBV can perpetuate a multi-generational cycle of violence and harm within communities.

The widespread health consequences of gender inequality place a massive burden on already strained public health systems.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the treatment of FGM complications alone costs global health systems approximately $1.4 billion per year.18 This moves the issue from a purely human rights concern to a fundamental public health and economic crisis. By addressing the root causes and consequences of GBV, the Tigray Project contributes directly to the sustainability of healthcare systems and the interruption of multi-generational cycles of harm.

3.2 Impediments to Economic Progress and Social Development

The failure to achieve gender parity has a direct and measurable economic cost. While women account for over 50% of Africa’s population, they generated only 33% of the continent’s collective GDP in 2018.20 This economic gap is not a result of a lack of ambition or effort, as nearly 50% of women in the non-agricultural labor force are entrepreneurs, and Africa is the only region where women are more likely than men to be entrepreneurs.9 Instead, their economic potential is hindered by systemic barriers.

Legal and financial discrimination are significant impediments to women’s economic progress. Women face unequal inheritance laws that restrict their access to land and property, which are crucial sources of wealth for securing financial stability for themselves and their children.9 They are also disproportionately affected by discriminatory housing policies and face significant barriers in accessing loans and credit to grow their businesses.9 The estimated economic cost of women’s diminished labor force participation is a staggering US$60 billion in annual losses for the African region.14 The research clearly indicates that investing in women’s economic empowerment is not a charitable act but a strategic macroeconomic policy.21 Closing the gender gap in employment and entrepreneurship could raise global GDP by over 20%.9 The “Laws-Jobs-Cash” framework provides a clear model for this, demonstrating how legal reform, job creation, and expanded financial access for women can lead to significant increases in economic productivity.9

The declining outcomes for women can be a crucial leading indicator of broader socio-economic woes to come, positioning women as the “canary in the coal mine” for the continent’s development. Therefore, the success of the Tigray Project would not only uplift young women but also serve as a barometer for the continent’s overall progress and stability.

IV. A Strategic Framework for Empowerment: The Tigray Project’s Approach

The challenges facing young African women and girls are deeply interconnected and cannot be addressed in isolation. The Tigray Project is designed as a multi-pillar initiative that tackles these issues holistically, grounded in a strategic framework informed by successful interventions and a nuanced understanding of the continent’s socio-cultural dynamics.

4.1 Pillar 1: Combating Violence through Legal Aid and Community Advocacy

The research reveals a significant gap between the existence of legal frameworks, such as the Maputo Protocol, and the reality of their implementation. Survivors of GBV face inadequate services, insufficient funding, and systemic barriers that make it difficult or impossible to access justice. The Tigray Project’s legal aid clinics are a direct response to this gap. The evidence provides compelling case studies of legal aid clinics empowering survivors to escape abusive situations, obtain justice, and return to school, as seen with a young girl in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A UNODC project in West Africa further demonstrated that supporting legal aid providers can not only help individual clients but also boost their institutional capacity, leading to expanded networks with law enforcement and the judiciary, thereby providing women with a more sustainable path to justice.

Beyond individual support, the project recognizes the need for community-wide change to dismantle the “socially normalized” nature of violence.5 The “One Man Can” campaign in South Africa offers a successful model for this, showing how engaging men and boys in advocacy can change harmful gender norms and reduce the prevalence of violence. The project will leverage similar strategies, including community education, door-to-door campaigns, and using media such as radio dramas to educate communities and shift mindsets. This dual approach of providing direct legal support to individuals while fostering broader community change is essential for creating lasting impact.

4.2 Pillar 2: Building Leadership through Mentorship and Skill Development

Recognizing that the continent’s future depends on a new generation of leaders, the project is designed to empower young women with the confidence, knowledge, and skills to lead. The research repeatedly calls for strategic investments in youth leadership, especially for young women.28 The Tigray Project’s mentorship program is a structured intervention designed to achieve this. Models such as the “Evolve” and “Step Up” programs provide powerful evidence for the efficacy of structured mentorship, with participants reporting significant increases in confidence (83%), career-readiness (84%), and a greater sense of community.30These programs provide a safe environment and offer bespoke content on topics such as self-esteem and career development, demonstrating a successful and replicable model.31

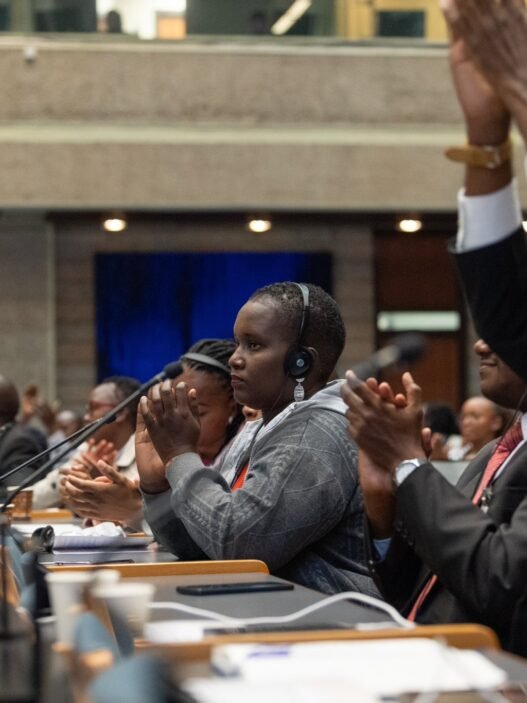

This pillar is aligned with the broader youth empowerment movement in Africa, which seeks to transform the burgeoning demographic of young people who are “Not in Education, Employment, or Training” (NEET) into “Doers”.32 The evidence highlights how a focus on the intersection of technology, education, and entrepreneurship can unlock the potential of the youth demographic.33 The report emphasizes the pivotal role of youth movements in driving systemic change, noting that over 10 dictatorships have been ended by youth movements in Africa and that these movements had a strong youth and women’s face.29 A critical conclusion from this is that an investment in young women political leaders is a fundamental investment in the future of democracy in Africa.29 The project’s leadership focus is therefore not just about creating female leaders but about cultivating a new, intergenerational, and resilient leadership model essential for a stable and prosperous continent.

4.3 Pillar 3: The Nexus of Education, Rights, and Opportunities

The Tigray Project will not address the identified challenges in a siloed manner. The research reinforces the need for a holistic, rights-based approach that links education directly to sexual and reproductive health, economic security, and freedom from violence. The UNAIDS “Education Plus” initiative provides a global blueprint for this strategy, outlining five key components to which every adolescent girl should be entitled.14The project will draw upon successful interventions that disrupt harmful norms and address economic realities. For example, research shows that providing cost-effective economic incentives to families, such as chickens or goats, can be highly effective in delaying child marriage and keeping girls in school.35 A study rigorously monitoring the costs of these programs found them to be both impactful and “cost-conscious and economical,” which is a crucial consideration for a scalable, sustainable model.36 The project will also advocate for key policy reforms that end the stigmatization of pregnant girls and violence survivors in schools, as called for by the “Education Plus” initiative.13

V. Strategic Recommendations and Implementation Model

5.1 Applying an Intersectional and Afro-feminist Lens

The Tigray Project’s implementation model must be sensitive to the unique and intersecting vulnerabilities faced by young women and girls across the continent. This requires a recognition of the specific challenges faced by those in rural areas, conflict zones, and those with disabilities.2 The project will adopt an Afro-feminist perspective, which acknowledges the intersectional nature of oppression—where gender is linked to race, class, ethnicity, and the legacies of colonialism.38 This approach prioritizes the specific needs and realities of African women, ensuring that advocacy strategies are grounded in local knowledge and cultural context.38This will involve working directly with grassroots organizations and engaging with local leaders to build a foundation of legal literacy and awareness within communities.38

5.2 Leveraging Technology and Partnerships

A key recommendation for the project is to harness the power of digital media for empowerment. A study in South Africa demonstrates that digital media is a critical tool for female youth to voice societal issues and bridge information gaps, fostering their active participation in socio-economic discourse.33 The project will also prioritize partnerships with grassroots organizations and feminist movements, such as those supported by the African Women’s Development Fund (AWDF).39 These organizations are often excluded from traditional funding opportunities but are essential for reaching communities and ensuring the relevance and local grounding of interventions.38 By leveraging technology and fostering strategic partnerships, the project can scale its impact and reach beyond urban centers to the most marginalized communities.

5.3 Measuring Impact for Sustainable Change

A robust monitoring and evaluation framework is crucial to ensure the project’s success. This framework must move “beyond numbers” and measure not only quantitative outcomes, such as enrollment rates and legal aid cases, but also qualitative shifts in attitudes, social norms, and the long-term empowerment of young women.22 This will ensure that the project is not just a short-term fix but a sustainable force for transformative change. The evaluation will be designed to measure the project’s capacity to disrupt the vicious cycles of poverty and violence and to foster a new generation of confident, knowledgeable, and effective female leaders.

VI. Conclusion: A Call to Action for a Liberated Future

The Tigray Project is not a stand-alone initiative but a critical component of the broader movement to unlock Africa’s potential. It is an evidence-based, strategic investment in a new generation of female leaders who are poised to drive economic growth, foster peace and security, and build a more just and equitable continent. The research presented in this report provides an unequivocal mandate for action. The challenges of gender-based violence, educational inequality, and political exclusion are not merely social issues; they are fundamental impediments to Africa’s development and stability.

The time for incremental change has passed. As a pan-African movement, the PAYM is uniquely positioned to lead this charge, leveraging its collective expertise and vision to transform the lives of young women and girls. The future of Africa is young and feminine, and the time to invest in it is now.